Using Anchor Texts to Distill Big Ideas Transcript

Speaker 1: Hi, how are you?

There are really 2 simultaneous purposes to today’s lesson.

You know, you all are really special because there are all these people here to watch you today.

We have adults in the classroom who are a part of this professional learning experience, and then we also have the lesson that’s going on.

Let’s talk about the lesson for today…

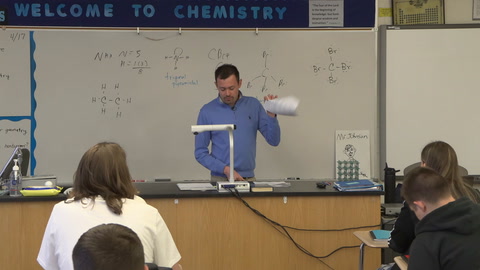

In this particular eleventh grade advanced placement literature course, the goal of the lesson was to have students wrestle with the question ‘Is evil ever justified in Heart of Darkness?’

By the end of our time together today we want to be able to learn how to connect some really specific details from the text to some ideas or concepts and answer a really tough essential question.

We began the lesson with looking at an advertisement. And this is not uncommon in my classroom.

Roll up, roll up, ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls for the crack of the whip against the animal’s stinging wounds! A big round of applause for the flaming hoops, the injuries, and the electric shocks!

I chose this particular advertisement because I thought a lot of the themes in it, a lot of the colors in it, actually corresponded to the themes in Heart of Darkness.

Ebbing animals as human caricatures clowning around, that’s no fun at all. It’s kind of startling, isn’t it?

Heart of Darkness is really dark. It’s very intense. It’s very controversial. And so is the advertisement.

Our brains usually do 3 things when we analyze regardless of what subject area it’s in. The first thing that we do is…

I generally start to introduce this process of making careful observations, finding patterns, drawing conclusions, because it’s just really central to students, again, being able to own their own process when it comes to thinking critically.

Because that’s what we’re going to do this today with Heart of Darkness, I actually wanted to practice with this first so we could all do it together once and kind of get the hang of it before we try to do that with what you’ve read. We’re going to go around the room one time. You cannot pass. And what I’m going to ask you to do is make some kind of observation about this image. All right? Anything that you see. Go ahead.

Speaker 2: They look sad.

Speaker 1: Hang on, I’m going to grab your words exactly, because you said a really important word there.

Speaker 3: He looks like he’s old, like he’s been there for a long time.

Speaker 1: How do you know he’s old?

Speaker 3: Well, his skin looks a little bit wrinkly.

Speaker 1: So, do you hear the difference between an observation and drawing a conclusion about it? He looks old, versus skin is wrinkly.

In this portion of the lesson, I was asking them to really focus on observations.

Speaker 4: He looks like he wants to escape.

Speaker 1: How do you know?

While it’s easy to jump right to kind of drawing conclusions on a text that’s very accessible, if we don’t understand our process very clearly, we won’t be able to replicate it when the text becomes more complex.

I love these moments where you don’t know how good you are yet, but you’re going to know here really quick.

We need to find some patterns in here. Are there any patterns in our observations here.

Speaker 5: A lot of the observations are focused on his eyes.

Speaker 1: Eyes. So that’s great. So what we would do is maybe find everything that has to do with his eyes. And then we would circle it. Has a tear. Looks sad. Eyes are pleading. So I want you to take a look at the list with the people close to you. And I want you see if you see any other kinds of patterns.

[crosstalk]

Speaker 6: It also looks like he's not washed, because some of the make-up is chipping.

Speaker 1: What are you noticing?

Speaker 7: There are some that described his age, like the gray hair in his chin.

Speaker 1: Oh, that’s great. Fantastic. What’s a pattern that you all have seen?

Speaker 8: He said, emotions and appearances?.

Speaker 1: Wonderful. Let’s hear, what’s another pattern that one of your groups came up with? I think I saw more than one group talk about mistreatment. Did any of your groups talk about mistreatment? Yeah? So what would we include in our pattern of mistreatment? Endless practices? Whips. I think we should include that one. Cages. No choice. Alone. So we’ve got a lot that has to do with mistreatment here. What other words can we use to describe mistreatment? Abuse.

While students were working on drawing conclusions, I also started to generate kind of a list of words. And the list of words were really conceptual words. Torture. It, again, became really important in making sure that we could move beyond the surface. That they can analyze. That they can think critically.

At your group, I want you to try to draw some conclusions about the ideas that this advertisement is trying to get across. What is it trying to teach us? So, at your groups you can talk.

Speaker 9: Kind of like when you go to a circus you think of it as happy because you see clowns and stuff like that, but you don’t really know what’s happening behind the scenes.

Speaker 10: So our enjoyment comes from others’ misery?

Speaker 11: So then they try to make us feel happy [things?]. And then they try to make us feel sad about them.

Speaker 12: Because it’s abusing the animals.

Speaker 11: Because they’re abusing the animals and putting them in cages.

Speaker 1: All right, let’s come back together. All right, I want to hear what you came up with. All right, so let’s start over here.

Speaker 12: We said that our enjoyment can come from others’ misery.

Speaker 1: Our enjoyment comes from others’ misery.

Speaker 13: We came up with Animal entertainment is animal enslavement.

Speaker 1: Wonderful, wonderful. Over here?

Speaker 13: Circuses are essentially prisons for animals.

Speaker 1: Really, really insightful. Lots of insight here.

So from the observation, actually the students went through, and they drew conclusions about the advertisement. And I thought that part was really powerful. Because it demonstrated that they really were drawing conclusions about these very same ideas that are in the text.

It’s really a powerful ad, isn’t it? Yeah, I mean it definitely is.

At that point, it’s time to introduce the essential question.

So here’s this question that I’ve been thinking about; that this advertisement makes me think about and that this book makes me think about. Can we talk about that for a second at your tables? Is evil ever justified?

So I put the essential question up on the board, I asked them to do some talking about it and just to have them start to unpack that question.

[crosstalk]

Speaker 14: Like a bank robber robbing a bank, that would be bad. But if it was Barak Obama doing something, it wouldn’t be as bad.

Speaker 15: It just depends on who’s doing it.

Speaker 16: Does that really make it okay because somebody who is richer did something terrible and someone who isn’t as rich did something terrible?

Speaker 15: It doesn’t make it better but it’s more [accepted?], because they have more money.

Speaker 16: Exactly. It shouldn’t be accepted, but it is.

Speaker 1: Hey, did you get some insights? Let me hear. I was able to pick up a few things. Let me hear, what’s your reaction to this question. Is evil ever justified?

Speaker 18: It sort of depends on the perspective it’s coming from, because it can be evil in your eyes but not in theirs.

Speaker 1: Absolutely. Take the advertisement, for example. From what perspective is that evil? From the animal’s perspective?

Speaker 19: And someone who knows.

Speaker 1: From who’s perspective is that not evil?

Speaker 20: The people that run it.

Speaker 1: The trainers who love the animals. Who else is that probably not evil to?

Students: [crosstalk]

Speaker 1: The ones making the money, the ones going to the circus, the spectators. So it has a lot to do with perspective, doesn’t it?

In hearing them talk about the advertisement, I was hearing them talk about some of the same things that go on in this novel. So I was really encouraged because I thought, This is going to be a really good foundation for when they start to look at some textual evidence.

I see all of these things that are so clear about that advertisement and then the conclusions that you drew. But now I’m wondering what this has to do with Heart of Darkness. Before we kind of move into the book here, I want you to see can you apply any of these concepts, any of these conclusions over here to Heart of Darkness? And talk about how you would apply it to Heart of Darkness. So do a little talking.

Speaker 21: Maybe, like, something better? Because Marlo’s always looking [up to him?].

Speaker 1: Oh, that’s really interesting. Did you hear what she just said? He’s a symbol for something better. Except that he also is what? He’s also evil. The man has heads on sticks for ornaments. So it’s really interesting, because it reminds me of what we just said about the advertisement. About perspective, about on one hand it’s not evil because some people are making money off these animals. And on the other hand, So that makes him really an interesting symbol then, doesn’t it? Because he kind of symbolizes something better, but he’s worse. So here’s the question I have for you: what does the pursuit of something better do to him? What does the pursuit of something better do to him? Will you think about that for me? So we’re going to get back into the books. We’re going to do a little investigation of evil, but I’m going to ask you to do a little moving around the classroom.

One of the changes that I made in the lesson was, I had originally intended to have these conver-stations that were really more like centers or stations and whole groups of students would go from one to the next. As the lesson unfolded, and I tried to pay attention to where their confidence was at and what we really needed to focus on, which was building that conceptual understanding, I realized that although there still needed to be movement in the class, I kind of needed to direct it more than I had anticipated.

You’re having these really great conversations but we need to kind of carry those conversations around. We’re going to do just a little rotation here. I’m going to have 2 of you rotate here, 2 of you rotate here.

So instead of having whole groups move and kind of work on these different things at asynchronous times, we did it all at the same time, but that’s when I decided to have 2 kids from each group kind of jump up and move. And each time there was a natural shift in that conversation, that became the conver-station instead.

We’re going to call these "conver-stations." Not just conversations, but conver-stations. The first one, you got to get back into your book. And I need you to pull some textual evidence. I want to see if you can find the 4 most powerful examples of evil. Got it? You think you can do it? Word for word. Everybody gets to write it down.

As soon as we are kind of creating this implicit hierarchy in the questions we ask students, that discernment is part of thinking critically. What’s your threshold for an example of evil? How do you know that you’re getting a really powerful example of evil?

Speaker 22: Anything that really connects with our idea of what’s evil in the world. And [in my opinion?], the white devil, we’re obviously evil.

Speaker 1: Good. Fantastic.

Speaker 23: You know I’m on page 81 and 82 that they called them savages and they described them as horrible people.

Speaker 22: When one has had to make [?] one comes to hate those savages?.

Speaker 23: That’s kind of what I have here, too.

Speaker 24: 183 I found, he described them as ‘black shapes.’

Speaker 1: One of the things that really strikes me about a question like ‘evil’ is that there is no easy answer. One of the ways that I really wanted to tackle this nuanced question was with a visual that also demonstrated this nuance.

I don’t know if you know about the word ‘evil.’ The word ‘evil’ comes from a Greek word that means ‘character’ and when they use character they actually mean like the imprint on a coin. Which meant that evil was something that was fixed, that you couldn’t change it. You either were or you weren’t. However, that’s not really how we see evil, is it? I think we generally see evil the way that we see color. You know how you can perceive different shades of red, you can perceive different shades of blue, those kinds of things? And I think evil is a lot like that. There are different shades of it and I actually think...

With a paint chip I asked students to list 4 things, one in each of those different colors.

We’re going to rotate here one more time, and when we do I’m going to ask you at the lightest color to put an example of evil. And the example can come from a quote. It can come from a conclusion. It can be a word. All right. So the least egregious to the most egregious. So we’re going to have 2 people move again to each, but 2 people who did move last time. Got it? All right. So, go ahead. 2 people move.

Speaker 25: So maybe we can do the darkest [kind?], so what would be the worst kind. Torture?

Speaker 26: I think [it's torture?], because the only thing worse than torture is death. You’d rather be dead than watching your mom being tortured or something.

Speaker 25: So [that's just like torture?].

Speaker 1: You can agree or disagree, but you don’t have to have the same ones in the same places. So you should talk about it. So you can agree or disagree, but everyone is going to have their own.

Speaker 27: It hurts more when you’re emotionally [stabbed?] rather than physically.

Speaker 28: Somebody could be smiling but on the inside they could be dying.

Speaker 27: They’re dying.

Speaker 1: All right. Let’s come back up here. We’ve been spending a lot of time doing this stuff over here. I want to make sure that you walk out of class today having pulled together this in some kind of idea that you can really hang on to. All right? So here’s a question: what is the impact of evil in the Heart of Darkness? What’s the impact of evil in Heart of Darkness? And this is the way that I’m going to ask you to answer it.

Originally the goal of the lesson was to have them leave with a really solid thesis statement. As the lesson progressed, I was so excited to really hear their conversations. And as I was going around and listening to their conversations, I realized how important those were to the way that they were developing concepts. So instead of spending more time at the very end talking about, ‘This is a formula for writing a thesis statement,’ I decided to let them keep their time.

I’m going to ask you to answer it using a couple of things.

And instead, just ask them to include 3 components to this response.

First of all, you need to have some kind of detail in your answer, something from the text. So, for example, it could be the use of the word ‘savage,’ the use of the word ‘devil,’ the description of the river.

And then we talked about these active verbs. And they are verbs that are important, because they are also thinking verbs.

So it has to be a word like ‘suggests,’ ‘Symbolizes,’ ‘conveys,’ ‘argues,’ those kind of words.

When we have those verbs in our responses, it forces us into analysis which, again, is the point of the whole lesson.

And then finally, you have to have some kind of concept in your response. So a concept has to be a word you can’t touch. So if you want to go from summary to analysis, you’ve got to have a concept in your response. Does that make sense? All right. So work on that. You can write it on the back of the paper.

It was really interesting to go around and listen to the students, especially as they were working on crafting these. Not surprisingly, it wasn’t hard for them to come up with the detail.

Well, what’s the idea?

Speaker 28: We’re saying that evil in the story is used to help move the story along.

Speaker 1: Oh, that’s really interesting.

Speaker 28: Because all the suffering that the characters have to go through gets them to a certain point in the story.

Speaker 1: So all of that is the detail.

Speaker 28: Oh, is it?

Speaker 1: It is, right. All of that is the detail.

But when I would say, ‘Oh, you’re not quite there, let’s get one of those verbs in there,’ and then to see how that pushed their thinking even further.

Suggesting that, offering that, arguing that…

It just is a reminder about how important a single word like that is to really pushing students to really analyze even more deeply.

Do you see how it pushes you a little bit further? All right. We’re going to play the stand up game, will everybody stand up? This is the stand up game. All right, you get to sit down if you choose to share your response. You get to sit down if you choose to share your response. Who’s up for it? Here we go.

Speaker 30: The Congo River symbolizes dehumanization because the people on the river are acting inhumane by treating other people...by being cruel to them.

Speaker 1: Absolutely. Got it. Nice, nice! Anybody else?

Speaker 31: The impact of evil in the Heart of Darkness is that it leads to dehumanization through greed, cruelty, and hatred, suggesting that the impact of cruelty upon the Congolese derived from greed.

Speaker 1: Wow, wow. That’s fantastic. Anybody else want to go? Yeah? You were working so hard on it.

Speaker 32: The evil in the story helps to move the story along, suggesting that evil in our environments and surroundings is necessary to help develop us into who we are.

Speaker 1: Nice, nice! I can’t believe you all did this in 90 minutes!

This lesson is primarily about thinking critically. And students have to learn how to think critically in order for us to release the responsibility of learning to them. In order to shift that agency for learning towards the student. In terms of kind of generating these very careful scaffolds for students to think about the nuances of evil, each of those steps help to facilitate a process in which students construct their own learning about this overarching question of evil in the novel.

Thank you so, so much for letting me be here with you. You blew me away. So give yourselves a hand. Give yourselves a hand. You were fantastic.

25 Comments

Katherine Chapp Mar 6, 2018 9:00am

Tanja Pick Oct 25, 2017 1:07am

Michelle Schlyder Jun 18, 2017 1:38am

Teri Smith Apr 14, 2017 10:27am

Diana Tan Alfonso Feb 11, 2017 5:50pm