Reading Like A Historian: Overview

Program Transcript

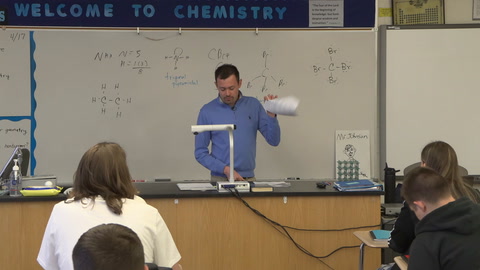

Will Colglazier:

Alright, welcome. Happy Thursday. So, what we’re going to do here is continue with our discussion of the March on Washington, so if you can take out that worksheet from yesterday and put your desk next to your partner, here come the documents… Document E––this is a good one! You’re going to like this one. Malcolm X… Okay, reliability: is this a speech that we’re going to believe? Before we even read it, what do you think?

Student:

Kind of. It’ll have some truth to it. But chances are, because it’s Malcolm X, there’ll be some incentive to antagonize Whites.

Colglazier:

Nice, nice… so the concept that he’ll have some truth, but he might have a bias to that truth. Okay, so Ferris is going to start us off, but follow along, of course, so we can hear what Malcolm X has to say about the March on Washington. Alright, take it away, Ferris.

Student:

(reading)

“The Negroes were out on the streets. They were talking about how they were going to march on Washington, march on the Senate, march on the White House, march on the Congress…”

Narrator:

Developed at Stanford University, Reading Like A Historian is a curriculum that engages students in historical inquiry via primary source documents. Instead of memorizing dates and facts, students explore different perspectives on historical events and learn to formulate interpretations backed by documentary evidence.

Will Colglazier (Interview):

So I guess history is conventionally taught in the sense that you have a teacher in front of the classroom, lecturing on material, telling the students what happened.

Shilpa Duvoor (Interview):

The Reading Like A Historian approach kind of turns that on its head, and what it says is that history is actually complex, and history is not just plain fact, it’s actually an aggregation of a bunch of peoples’ opinions and perspectives.

Duvoor:

We’re going to read two documents that describe Gandhi’s philosophy and a document that describes Ho Chi Minh’s philosophy. So, these are two people who, faced with injustice––right?––faced with imperialism, the colonizers, who are occupying their country, have tried to figure out, “What is the best way for me to gain my freedom?”

Valerie Ziegler (Interview):

I would describe Reading Like A Historian as an approach to historical thinking, and––historical thinking being the skills that historians use––and so historians think about the type of documents they’re reading, and they use skills to do that: you know, they will ‘source,’ or ‘when was it written, why was it written?’ They also think about the context of the time. And so Reading Like A Historian takes those basic skills, and brings it to a classroom for students to answer a fundamental question.

Sam Wineburg (Interview):

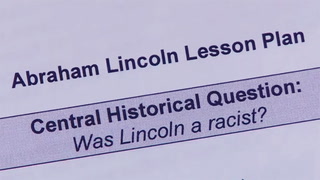

The first thing that this program does, that’s very different from a conventional history class, is that it turns history into a series of questions rather than a series of answers.

Ziegler:

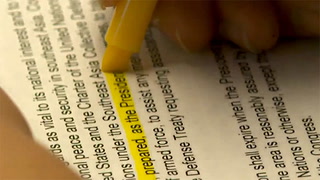

On your timeline, I’d like you to write today’s question, so we make sure we’re constantly coming back to this as we look at it. And the question is: Was the U.S. planning to go to war with Vietnam before the Gulf of Tonkin?

Ziegler (Interview):

Then you begin using the skills of Reading Like A Historian. So we always begin with sourcing it, trying to understand who wrote this document and what was their intent in it.

Ziegler:

And we’re going to begin with the Gulf Of Tonkin Resolution. That’s going to be our first document.

Sam Wineburg (Interview):

So what I discovered is that historians and very good high school readers actually look at historical texts in quite different ways. Historians, for example, look at a document and immediately read the first few words and go down to the bottom of the document, and ask themselves questions like, “Who wrote this? When was it written? What else would I need to know to make a considered and valued judgment?”

Student:

Because it’s a memoir and it’s based on his recollection, he may have some, like, holes in his knowledge or… Because of his bias––he was an activist––he may try to, like, exaggerate maybe.

Sam Wineburg (Interview):

Sourcing is simply the notion that before we accept information as fact or true, we ask a series of elementary questions: who wrote the information, where did it come from, when was it written, by whom, et cetera.

Shilpa Duvoor (Interview):

In general I’ve found that a lot of my students actually enjoy reading primary source documents because they find it a lot more interesting; they find they actually understand the material a lot better because they really feel like they are getting the perspective of somebody who went through that time period.

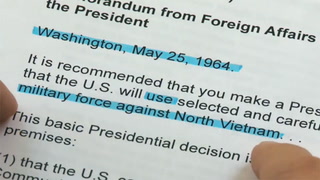

Student:

It’s not like—not even the Gulf of Tonkin has happened yet, and it’s already saying to use military force against Vietnam. I think that this whole document’s going to be about going to war.

Student:

So they’re already speaking about war before anything happens.

Student:

Yeah. Because it’s supposedly, like, the basic presidential decision.

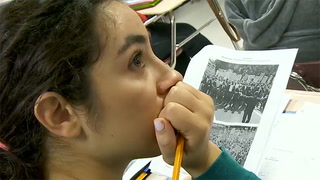

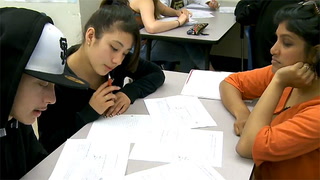

Student (Interview):

Working with this primary documents, sometimes it’s harder, and depending on the subject, ‘cause sometimes the document might not give you a lot of details about it. Well, it makes you think more, which makes it a little bit harder, but at the same time, it makes it easier to learn the subject.

Shilpa Duvoor (Interview):

So the three skills we focused on this year are sourcing, contextualization or context, and corroboration. And the context is everything that’s happening at that general time period and trying to bring in all the information of a particular time period to a document or a textbook passage that you are reading.

Duvoor:

Let’s go quickly to #3: “Taking into account the context of the time period”––so everything we brainstormed at the very top, okay?––“and everything the British have done to the Indians, would you support Gandhi’s philosophy, if you were an Indian person at that time period?

Student:

At that time, it would probably—I’d probably be too angry to agree with Gandhi’s philosophy.

Duvoor:

Give me a piece of context that we brainstormed in the beginning. What were some of those things that made you angry?

Student:

Um, like, the Salt Tax… um, the massacre… the fact that we had to farm for somebody else, we couldn’t even farm for ourselves.

Duvoor:

Um-hmm! There were really mixed feelings at this time on Gandhi’s philosophy.

Valerie Ziegler (Interview):

And then, the final part becomes this, sort of, what we call corroboration, comparing these documents. So how can we answer this question, taking everything that we just read and all this knowledge that we have, to try and compare and contrast these documents to come to an answer.

Colglazier:

So, was our guess confirmed that he was going to criticize the March on Washington? Absolutely. So what did he say?

Student:

Like, he said they controlled it so tight.

Colglazier:

And who controlled it? Who’s ‘they’?

Student:

Like, the president.

Colglazier:

Good! So the White government, right?

Student:

Yeah.

Colglazier:

What was he hoping the March on Washington would be like?

Student:

It would shut down the government and the airport and other, you know, large organizations… cause massive, like, economic and political stagnation.

Colglazier:

Massive disruption! Is that what happened? No. So he’s pissed. Okay. Well, let’s look at Document F to corroborate. And what’s the best way to corroborate a public speech?

Student:

Something private.

Colglazier:

Something that’s private. I like it, Rachel. And what we have here is the Kennedy Tapes. So, here is a meeting in the White House on August 28, 1963…

Will Colglazier (Interview):

I think they appreciate the fact that they’re investigating what happened, without just being told, and I tell them, you know, they’re like CSI detectives. It’s not DNA and fingerprints, but it’s, you know, speeches and diaries and these audio clips that are their evidence to determine, you know, what really happened.

Valerie Zielger (Interview):

Students love to debate. I tell them that I’m tricking them in some ways because they’re debating history, but they’re really debating important questions in history, um… but they also like to recognize that their classmates have made a good point, but they also like to be recognized for their original thought.

Ziegler:

Why did people oppose the Vietnam War? Was it mainly for social, political, or economic?

Student:

I think it was political because the citizens of the United States just disagreed with the war because the presidents weren’t doing what they wanted them to be doing at the time. In Document B…

Student (Interview):

When we’re investigating the questions it feels like we’re actually in that time period, like, we get to understand how the people felt during the time. And we won’t have to think about how we think now, and try to translate it to how they felt in the past.

Student (Interview):

It actually has kind of changed my way of thinking because there’s always––every single thing that happens in life, there’s not always one point of view like––I might see something, you might see it differently. There’s always two points—more than two or two points of views on every single situation going on in life.

Sam Wineburg (Interview):

The act of teaching students that there isn’t a single right answer can, for some teachers, complicate the process of teaching. But our response to that is to appeal to teachers’ highest calling, which is––the people who go into history teaching––is because they want to improve a democratic society.

Colglazier:

Is Malcolm X right? Is this thing a sell-out? Is this thing—I mean, they didn’t lay down in the streets. They didn’t lay down in the government, on the runways. Does that make it ineffective?

Student:

Uh, no. Because even though it happened peacefully, it might be a little bit of a sell-out, like you said, but it was something, like, peaceful, but it turned out to be, like, great, and the point where it starts to kind of change the viewpoint of people.

Colglazier:

Yeah, so maybe by giving in a little, by “selling out” a little and getting Kennedy to support it, they actually still got a lot out of it. What do we do with Malcolm X’s comments, then?

Student:

Um, that he was right, that they give in a little bit.

Colglazier:

Good, so you’re not going to sweep it under the rug, right? You’re not going to silence it. You’re going to include it. And then you wonder why textbooks don’t.

Sam Wineburg (Interview):

So Reading Like A Historian is an attempt to treat high school and middle school students with respect. Rather than giving them worksheets and pat answers that they have to repeat from the textbook, it teaches them how to use their minds well, by allowing them to come to their own conclusions by examining original documents and engaging the best of their intellectual capabilities.

#####

109 Comments

Gauri Sehgal Oct 12, 2021 11:05am

Inquiry method is very useful to get the attention of students, brainstorm on issues and express their opinions and perspectives.

The questions need to be framed very carefully, so that they motivate the students to keep thinking while they discuss and share their point of view. This method of teaching History, or rather teaching any subject, involves the students at each level . The students are reading the text and undertsanding the perspective and experiences of the author of the text.

This method makes the Teaching -learning process much more interesting as compared to the conventional method of simply providing information to the students. It can be used for any subject/topic where the students have the freedom to express/ reason their thoughts and accept others opinions.

Linda Richelson Sep 7, 2021 9:35pm

The inquiry approach engages students. It asks for their opinion and encourages them to form an opinion and share their thinking. If they are not sure, the document provides information that can help them achieve this.

When students are taught history, or any other subject, as a series of answers, it doesn't encourage inquiry. It encourages memorization or, at the least, boredom. The student is expected to accept what the author was thinking whether they agree with it or not.

I use this approach when I teach college level business classes. Students should be encouraged to inquire. If they read a text, a fiction or non fiction book or are presented with scientific theory, they will benefit from understanding the genesis of the document so they can determine the validity the work has for them.

Amarendra Mishra Aug 26, 2021 8:23am

Inquiry approach is thought provoking. Any thing that is thought provoking involves undivided attention.Hence it is always engaging.

Questioning leads to more exploration and individualised learning.

This approach can be applied to all subjects as experiential learning

John Sanders Aug 1, 2021 6:39am

This is the classic learning environment, teacher led classroom. History might be suited to this because the "facts" can be delivered formally by the teacher, the students can independently research the topic, and the perspective is facilitated by groups within the class who get the chance to voice and prove their perspective views. The individual alone can't experience the different perspectives which transform history as remembered or researched by a history writer. On the other hand, history doesn't lend itself to a consensus view.