Reading Like A Historian: Corroboration

Program Transcript

Will Colglazier:

Welcome. Happy Thursday.

Will Colglazier (Interview):

You know, historical thinking is a student that can understand that one document is not going to give me all the answers—I need to corroborate documents—and that was a part of the lesson today, that a full story must be told from multiple documents, and that the documents that are going to tell the story best are the ones that we deem more reliable than others.

Colglazier:

What we’re going to work on today is the March on Washington. So you do not need a piece of binder paper. All you need is the worksheet I’m giving to you right now. The best place to start our lesson on the March on Washington is to look at what we already know about it. I’d like you to just put down everything you know. If you’re unsure whether it’s right or wrong, I don’t care, put it down. Alright, what do we know, or think we know, about the March on Washington? Josh?

Student:

Led by Martin Luther King.

Colglazier:

Led by MLK. What else do we know? Nuku?

Student:

Thousands of people participated.

Colglazier:

Thousands… a shot in the dark, Nuku, how many?

Student:

200,000?

Colglazier:

200,000. If we’re going to corroborate this, what’s a good place to look at?

Student:

The documents.

Colglazier:

Your documents! But come on, if I’m a, quote-unquote, history teacher, where am I going to make you look?

Student:

The text book.

Colglazier:

Text book. Let’s do it. Move your desks next to your partner.

Will Colglazier (Interview):

So I guess the basic idea of the Reading Like A Historian approach is that history is not a simple story, that it’s not a set of facts that happen that students have to remember to regurgitate on a test. I see the content as being important but a means to a different end, a means to an end of skill development, specifically being able to critically think about information.

Student:

“Do you consider the textbook excerpt reliable? Why, or why not?” I don’t think so, because it’s a textbook, and textbooks are usually watered down and sugarcoated a lot. And for something that’s so big, it only takes up, like, 5 lines, so it’s not that reliable.

Colglazier:

Alright, so what we’re, again, trying to do here is corroborate with what we already know. So, this is what we came up with before. Let’s see what the textbook excerpts say. Josh?

Student:

Organized by A. Philip Randolph.

Colglazier:

Okay, so—and actually, you were the one who said it was led by MLK, but we get this new ripple that A. Philip Randolph is in the picture. Every single group here… six different textbooks, they’re all right here—boom,boom, boom—I could go on and on. And what do they all say? Pretty much the same thing, right? You love corroboration, you’re saying, “Six different textbooks say the same thing,” I like it. How many people’s groups mentioned A. Philip Randolph? Two out of six. So we’ve got some names in here that are not in four but are in only two. What do we think about that in terms of reliability?

Student:

Not reliable.

Colglazier:

Why? Why, Lauren?

Student:

I think it’s more sugarcoated than anything.

Colglazier:

Okay, so you think they kind of, like, fluffed it up?

Student:

Yeah, like, they don’t really know.

Colglazier:

So, why would one textbook not mention A. Philip Randolph but another textbook would?

Student:

Biased.

Colglazier:

Bias, maybe they don’t like the man. Maritza?

Student:

Instead of giving credit to him, they want to give it to Martin Luther King, because he’s more popular.

Colglazier:

Ah! So they would want to give Martin Luther King more attention because he’s more popular! How many people here knew about Martin Luther King’s “I Have A Dream” speech before they walked into my classroom? Everyone, right? So, for Question 3, in terms of reliability, what might we put in there?

Student:

So, I think that the general basics of it is pretty solid and reliable, but we shouldn’t stop here. We should go on.

Colglazier:

Why should we not stop here?

Student:

Because it’s pretty simplified.

Colglazier:

Ah! I like it! Look how small these excerpts are, right? The March on Washington—boop!—one paragraph. Pretty small. And so we obviously need to corroborate more documents. So, let’s do so. Alright, yay. What’s your historical question? What’s the true story behind the March on Washington? And so, you see that blank, where it says “Part 3 – Historical Question?” I think there’s some layers to the March on Washington that we don’t know about. We seem to have some of the basics. You knew some of the basics before you walked in, right? “I Have A Dream” speech, Martin Luther King—but there seems to be maybe some other stuff about it that we don’t know, and we want to make that a little bit more of a full story.

Will Colglazier (Interview):

So, the question hooks the students so that they have a purpose to the class. By having this focus question, they know the direction of what they have to do, and they understand that the answer’s not going to come from me but it’s going to come from documents, it’s going to come from the history itself. They’re going to have to investigate it and find it out.

Colglazier:

Alright, so what I need you to do right now is Document A, the first row.

Student,

Wait, Mr. Colglazier? 1 is very reliable, and then 4 is…?

Colglazier:

Right, so 1… “you bet your life,” right? 4… “it’s trash, I’m going to throw it away.”

Student:

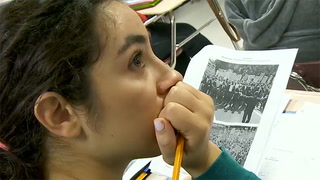

Oh, alright, yeah. There’s no way that they could lie in these pictures, so we should put a 1.

Student:

I put a 2, because it doesn’t say who took the picture.

Student:

Why?

Student:

Because the source isn’t specified.

Student:

Yeah, it’s not really specific, the source, and also the people could be, like, staged.

Colglazier:

Alright, what are we thinking here? What are we thinking about reliability? What do you think about reliability, Joe?

Student:

I gave it a 2 because I feel like it could be, like, photoshopped.

Colglazier:

Photoshop, so, meaning someone digitally—

Student:

Messing with it, yeah.

Colglazier:

Okay. True.

Student:

But then, like, they could just be straight-up pictures of what actually happened.

Colglazier:

But why a 2 and not a 3? Like, what made you edge more towards reliability?

Student:

Because the pictures seemed to fit the background information we had.

Colglazier:

Oh, nice! So the picture corroborates what you already know. Make sense, okay. Ryan, you gave it a 1 with Danielle. Why?

Student:

Because, the—it was taken, like, it was taken there.

Colglazier:

It was staged, they were there, right?

Student:

And there’s too many people to stage it.

Colglazier:

Ah, so this looks—you can’t fake this, right?

Student:

Yeah.

Colglazier:

It’s a picture. A picture’s worth a thousand words. Well, let’s continue and see if these pictures—we can actually deem them reliable or unreliable by looking at Document B. So, flip it over. Document B comes from this book. It’s a book by John Lewis. So, he is an activist in the Civil Rights Movement at the time. Today he is a politician in the House of Representatives, alright? Again, I am going to ask you to think about reliability, so why don’t we go ahead and fill in that first box, even before we read it.

Student:

Well, because it’s a memoir and it’s based on his recollection, he may have some, like, holes in his knowledge or… because of his bias—he was an activist—he may try to, like, exaggerate, maybe?

Colglazier:

So what we need to do is read it, and then we can go back to our educated guess and determine if we were right. Okay? Alright, Kyle, start us off. And please follow along. And of course, what we’re trying to do is answer that same question: What is the true story behind the March on Washington? Alright, Kyle, start us off.

Student:

(reading)

“‘Walking With The Wind: A Memoir of the Movement,’ by John Lewis, 1998. The day of the march, we met for breakfast, then we went as a group to Capitol Hill to pay a call on congressional leaders…”

Student:

(reading)

“In this case, some people wanted to be as close as possible to A. Philip Randolph, the head of the March on Washington, who was the focal point this day. Even Dr. King was pushed toward the side.”

Colglazier:

Martin Luther King was pushed to the side. Wait! I’m a little confused. We look at this picture, he’s directly in the middle. Let’s fast-forward real quick to Document C. Here, it pulls back a little bit and we see King, here, now a little bit more towards the side of this picture. If you, a little like CSI investigators, if you look at the road, you see one line here on the road. Right here you see a double line on the road. What does that mean, Megan?

Student:

Middle of the road.

Colglazier:

Middle of the road is where the double line is, and who’s standing on the middle of the road? Can someone name this person?

[student murmurs]

Colglazier:

Good guess. But who’s in the middle of this? A. Philip Randolph. King is at the side. The document by John Lewis tell us, who is this guy? What’s he doing?

Student:

Oh, he’s a photographer.

Colglazier:

He’s not the photographer, but he is trying to make space for the photographers. Look at Doc. C, the pictures. You can see that what we have here is a big truck full of photographers, and they’re trying to create space so the photographers can take pictures of the march, as if that’s the front of the march.

Will Colglazier (Interview):

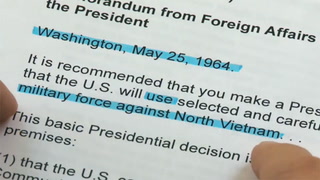

Then we move in on the program, the primary document. And they get content information that there were more speakers that day, that A. Phillip Randolph had the opening remarks and the last pledge, so he obviously is important.

Colglazier:

So, probably one of the most difficult questions of the day, for you to kind of get in that second box, but try your best with your partner: What do you think… what do we need to add to our story of the March on Washington from what we just heard? LeAnn, what do you think?

Student:

I think that there was… the main point was that there was a specific purpose for having the march. They wanted the FEPC bill passed. So it wasn’t just that they wanted civil rights. They wanted a specific bill.

Colglazier:

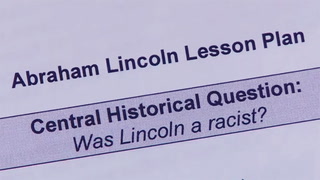

Good! In the textbook excerpts, other sources, we just hear about the de-segregation, right? If you look at the program in Document D, what’s the technical name of the March on Washington? “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” not “March on Washington for Freedom and Jobs.” It’s “Jobs and Freedom,” so the concept of employment is a key part of the March on Washington. To not put that in there is to misunderstand it.

Will Colglazier (Interview):

The layers of life begin to unfold when they start to realize that everything that they read is not, you know, completely true, that they need to assess reliability constantly. And they begin to understand and see the process, especially when you give them these contradictions where they are not given the right answer. Whereas a traditional teacher might just say, “This is what happened at the Battle of Lexington,” you know, have them figure it out, and then they become detectives. And I think giving them these skills make them, you know, more informed.

#####

12 Comments

Mallory McDonald Oct 7, 2020 1:25pm

1. Corroboration is an essential skill because one document cannot give you all of the answers to a question.

2. This lesson challenges the students' ideas of truth because some documents can leave out important details that can create a bias or untruthfulness to what actually happened.

3. It is important for students to incestigate a wide variety of sources becasue they need it to see the big picture of historical events.

Ceson Ponder Sep 2, 2018 9:18am

As a history teacher this may be one of the best lessons I've watched yet...and most helpful.....I lead a computer based course so it's even worse....it's a continual fight to get mys students off screen time to refenernce actual documents and and reliable scholarly sources. They thing everyhting on the internet is reliable....-_-......it's even worse now

gwen purvis Dec 7, 2017 10:43pm

Courtney Durrant Nov 21, 2017 12:22pm

Megan Humphrey Jan 18, 2017 3:38pm